On the first Earth Day in 1970, my brothers Dave, Rick, and I were coming of age in the North Country. Our younger two brothers, Dan and Kenny, were twelve and five. We lived in a historic home a short walk from Lake Superior in Duluth, Minnesota, along Tischer Creek, bordering Congdon Park. We could see the iron ore boats on the lake from the second and third floors of our house. From just about anyplace, we could hear the low reverberations of foghorns passing through or approaching the lift bridge. We lived just one block away from East Duluth High School. Our dad, Charlie Aguar, was a city and county planner who had a firm downtown with three partners—Aguar, Jyring, Whiteman & Moser, Inc. He frequently worked on the Mesabi Iron Range, planning an interpretive center. Other trips were to Ojibwe territory. He also planned pedestrian areas in downtown Duluth and changes at Lief Ericson Park that were initiated a decade or more after we left the area.

I was mostly oblivious to Dad’s work. All I knew was that he was out of town more days than he was at home, and that none of us were allowed to disturb him when he was in his study. One of my closest friends was surprised once to hear that I had a father, because she had never seen or met him. My mother was always home.

I was not an athletic girl. I always had my head buried in a book. Besides reading, I loved observing wildlife, walking to and on Lake Superior's north shore, playing the cello, and writing stories and letters. I had already written one or two letters to the editor of the Duluth News Tribune and a couple to Senator Fritz (Walter) Mondale, urging him to run for President. When I was feeling teenage angst, I sat on a large gray boulder alongside Tischer Creek, listening to the music of the rapidly moving water and inhaling the smell of negative ozone ions. Typically, our tuxedo cat, Pandy, followed and joined me, making everything right in my world. That was truly my happy place.

Tischer Creek was pristine back then, supporting large runs of glistening Brook Trout and small, colorful Rainbow Smelt. Smelting parties in Lake Superior waters in Duluth, Minnesota, rival the energy of Bulldog football home games in Athens, Georgia. The smelt run in April after the lake thaws and spawning begins. Smelt are light sensitive and move to shallow waters, so harvesting occurs at night. This generally follows the imbibing of large quantities of beer, with fishermen (typically not women) in hip-waders walking backward into the water while carrying large nets that will hold several gallons of smelt. What could go wrong? Injuries from slipping on large rocks and even drowning were not unknown. Smelt runs peaked in the 60s and 70s but are less bountiful now.

Even in High School, I liked to organize things and invite others into my world. I have just the vaguest memories of initiating a club in tenth grade with my twin brother, Rick, to promote taking care of the planet in small ways. The club was called Students to Oppose Pollution, and the acronym was STOP. We talked about pesticides, picked up litter, and recycled. Recycling was considered controversial. St. Louis County didn’t implement curbside pickup of recyclables until the 1980s.

My brother Rick reminded me that the club also focused on the negative impact of taconite mines, part of the steel-making process. Taconite tailings were dumped into Lake Superior, altering the ecosystem in several ways. The fine particles cause turbidity, or cloudiness, in the water, making it less transparent. Taconite particles can clog fish gills and stunt their growth. Turbid water absorbs more heat than clear water. That, in turn, reduces dissolved oxygen levels. The fibers also have asbestos-like qualities that degrade the environment.

One year after that first Earth Day, a lawsuit was filed, The United States vs. Reserve Mining—a case that changed modern environmentalism. However, environmental hazards continue in the formerly pristine lakes of Minnesota. Just last year, in the summer of 2024, there was a tragic fish kill in my beloved Tischer Creek. The cause was an intentional dump of chlorinated water into the creek by the city of Duluth. That investigation is ongoing.

Back to April 22, 1970, and the first Earth Day. I remember or imagine that I approached the administration of East High School with a request to hold a school-wide assembly for the first Earth Day. It was a long time ago. I am clear that permission was given only if the assembly was optional, and each teacher consented that their students attend. I don’t remember if any adult leadership organized the event, or if it was entirely student-led. I do recall that my drama teacher gave a firm no to my request. He commented, “hippy nonsense.” This embarrassed me, given the preparations I was making. I decided to ignore him and accept the consequences later. Fortunately, he accepted my manufactured excuse.

My memories of the first Earth Day are limited to a presentation involving my dad and siblings, Dave and Rick. It included a presentation combining lights, slides, and a spoken presentation, culminating with slides and the soundtrack of Simon and Garfunkel’s Bridge over Troubled Water released that year. It sent chills down my spine. The slides depicted images of our beautiful American environment contrasted with spoiled areas, junk yards, and polluted spaces. Later in the day, Charlie gave a presentation at a local college.

I’m linking to a history of Earth Day, conceived of by Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin. In addition, you can hear an audio interview of Senator Gaylord at UGA in Athens, Georgia here. Eugene Odum, the father of modern Ecology, is now recognized as the father of the Eugene P. Odum School of Ecology at the University of Georgia. It began in 1967 as the Institute of Ecology. In 1969, the School of Environmental Design was opened by Hubert Bond Owens. The first Earth Day occurred during the 1969-70 school year.

Dr. Odum was a friend of Senator Gaylord, and they communicated about the need to add professional practice to the curriculum at the School of Environmental Design. Odum contacted my dad to find out if he was interested in teaching. He was excited to see the students' response to Earth Day and curious about how he could apply his skill set. He met with Owens and Odum and accepted a professorial teaching position.

Within five months, on August 19th, my brother Rick and I arrived in Athens and enrolled at Clarke Central High School. It was the first year of mandated racial integration in Clarke County. Dave married his high school sweetheart, Diane, before we left. They moved into the lower apartment at the Taylor-Grady House as caretakers. Danny enrolled in Clarke Junior High School, and Kenny started kindergarten.

Charlie got his students involved with various projects and practical presentations, juried by their peers and other professors. In 1972, Dad and other visionaries set in motion a plan to save swamp land from being drained, populated with apartments and shopping centers, and converted to a Nature Center instead. It became a reality in 1977.

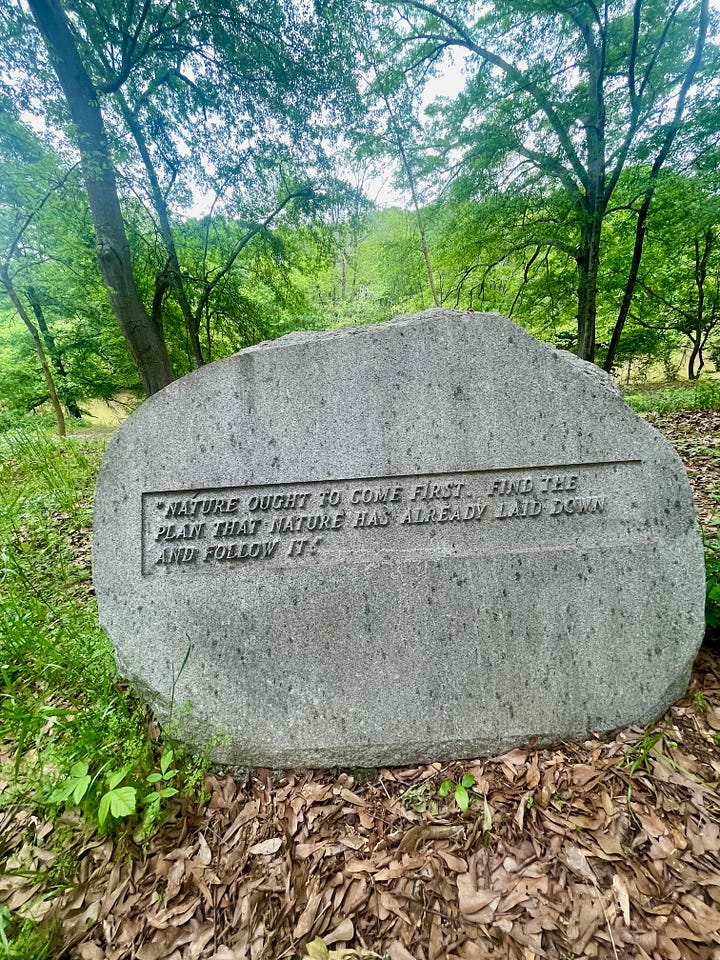

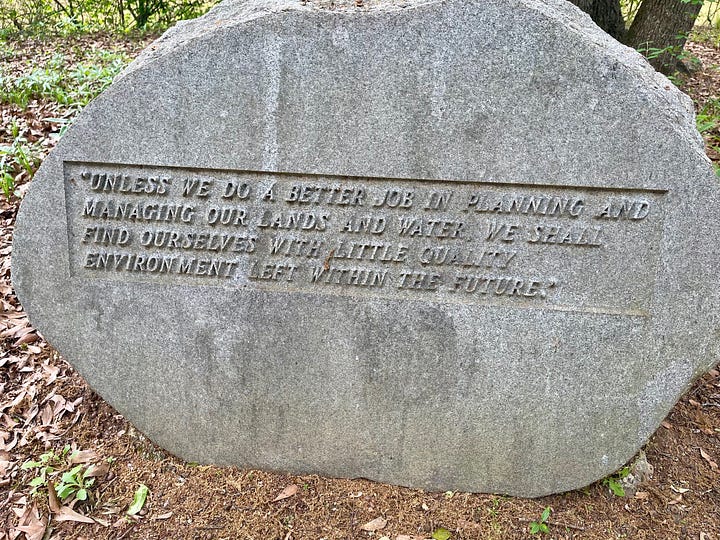

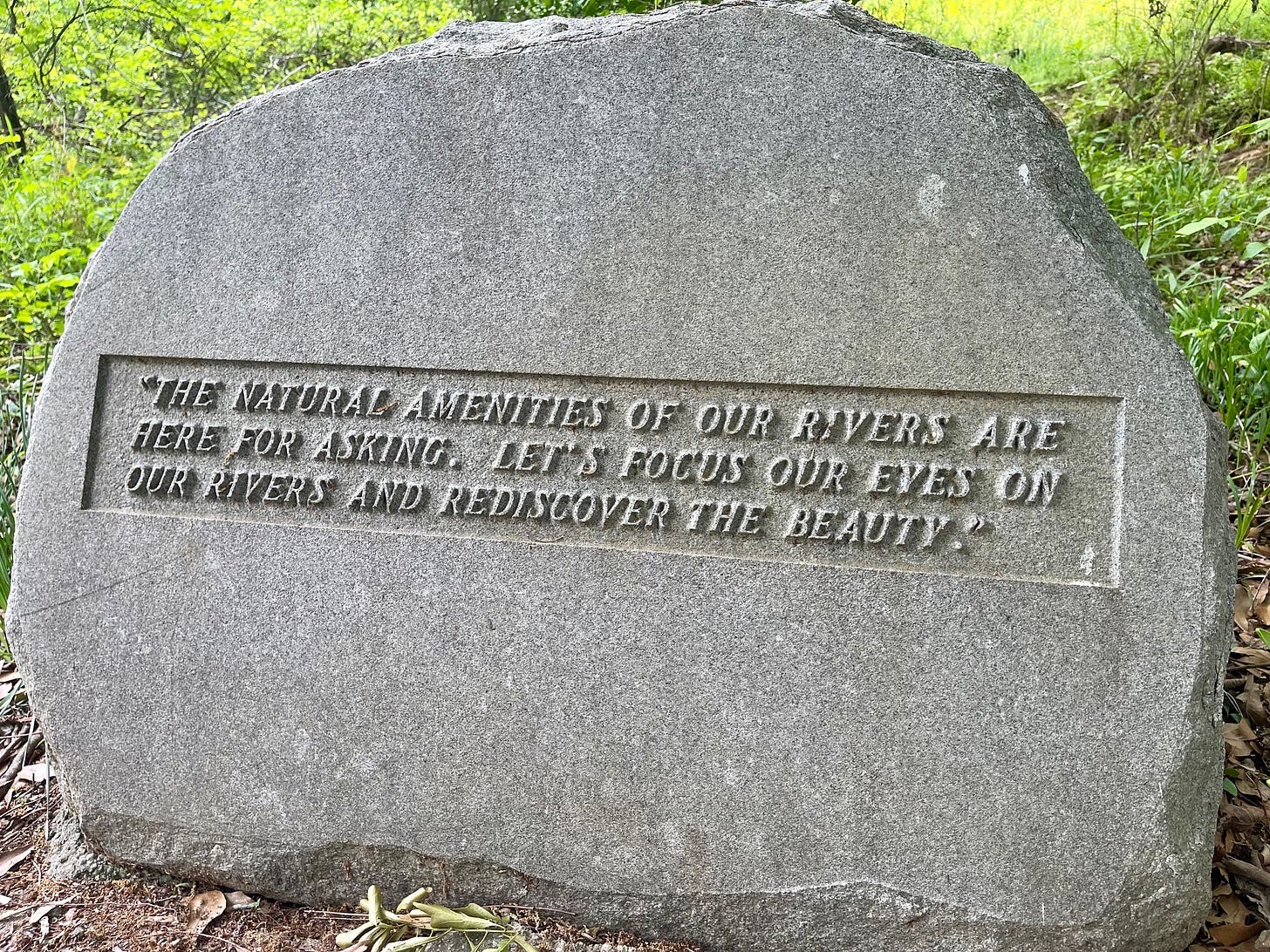

Dad also set out in the early 70s to promote a Greenway System for the North Oconee River. He is called the “Father of the Greenway” in Clarke County. Unfortunately, it took about thirty years to become a reality, and Dad passed away just four months after ground was broken and before any part of the Greenway was built. In 2004, the Aguar Plaza was opened in honor of Charlie Aguar’s impact on the project. At its inception, it had clear walking paths with granite monuments carved with quotes from my father’s writing and speaking, and places to sit and reflect. Invasive weeds have since moved in, along with homeless encampments.

L-R 2004 Reveal of Aguar Plaza: Nate Aguar, Dave Aguar (deceased), Kiley Aguar,

Dan Aguar, Berdeana Aguar (deceased), Tessa Aguar, Cathy Payne, Rick Aguar

April 22, 2025, marked the fifty-fifth anniversary of Earth Day. These days, Earth Day is well-established, and in many communities, April is celebrated as Earth Month. For the Athens-Clarke County workers, it is a holiday. This Tuesday, one of our local Rotary Clubs and the Athens-Clarke County Trails and Open Spaces department held an Earth Day event to clean up the Aguar Plaza. I was excited to see friends, Clarke County employees, and young volunteers there. Rotary Club of Athens West members came, including Dick Field, who helped plan and finance the plaza. My brother Rick, nephew Forrest, and I pitched in. It looked much better when we left than when we arrived. I am grateful. I hope this can be more than an annual event. It has been twenty-one years since the plaza opened.

Here is a Vimeo video about the opening of the Greenway, the opening of and the decline of Aguar Plaza. Several Aguar family members were involved in the video. It includes clips of my dad, mom, siblings, nephews, aunt, Professor Al Ike, Dick Field, two Athens Mayors, Walter Cook, and more. It ends with my brother Dan’s sense of humor, on Ken’s birthday, which falls on Valentine’s Day.

Earth Day brought the Aguar family to Athens, Georgia, and Charlie became a gift to the community. Each family member has done their part to continue a legacy that includes caring for the environment.

Thank you for reading this very long post.

“CHARLES E. AGUAR, 1926—2000 VISIONARY EDUCATOR NATURALIST HISTORIAN PHOTOGRAPHER VETERAN REGIONAL PLANNER ENVIRONMENTAL STEWARD COMMUNITY ADVOCATE AND VOLUNTEER

Charlie championed the idea of a Greenway System in Clarke County through his vision, teaching, and volunteer service. [He was] one of the original founders of the Greenway Commission in 1989. He was present for the November 1, 1999 groundbreaking at [the] site.

Our thanks to Rotary Club of Athens West, Oconee Rivers Greenway Commission, and the friends, volunteers, and supporters whose generosity made this possible.”

Touching tribute to your dad & Earth day. What a legacy!

Great article, Cathy! Loved seeing the photos and hearing your story.